Disclaimer:

This guide is intended to provide you with information only. If you have a legal problem, you should get legal advice from a lawyer. Legal Aid Queensland believes the information provided is accurate as at March 2023 and does not accept responsibility for any errors or omissions.

We are committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders from all culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. If you would like this publication explained in your language, please phone the Translating and Interpreting Service on 13 14 50 to speak to an interpreter. Ask them to connect you to Legal Aid Queensland on 1800 998 980. If you are deaf or have a hearing or speech impairment you can contact us using the National Relay Service. Visit www.accesshub.gov.au and ask for 1800 998 980 (our legal information line). These are free services.

How can this guide help me?

This guide can help you if you’ve experienced domestic or family violence and want to get a domestic violence order or learn more about your rights.

Do I need to get legal advice?

Yes. You should get legal advice before starting the process to get a domestic violence order. A lawyer can help you understand the process and the steps you need to take. They can also give you information and advice that is specific to your circumstances.

How can I get legal advice?

You can get legal advice from:

The person who wants protection is called the ‘aggrieved’. The person reported to have committed domestic violence is called the ‘respondent’. We will use these terms throughout this guide.

What can I do if I need help urgently?

Call the police

If you are in danger and need urgent help, call the police on 000. If you want information about accommodation in a women’s refuge, call DVConnect on 1800 811 811.

Make a safety plan

If you are worried about your safety or your children’s safety, you should consider making a safety plan to use in case you need to leave your home or a situation quickly. It is important not to let the person you are afraid of know your plans. You might find it useful to develop the safety plan with a domestic violence support worker. We have included phone numbers at the back of this booklet.

What goes in the safety plan?

- Talk with someone you trust (confidentially) about the abuse and identify who can support you when you feel particularly vulnerable.

- Decide who you will call if you feel threatened or in danger. Keep those phone numbers in a safe and handy place.

- Decide where you will go if you need a safe place. Think about whether you could stay with a friend or family member or go to a women’s shelter or crisis accommodation.

- Decide what arrangements you will make to ensure your children and pets are safe.

- Know the easiest escape routes from your home, including windows, doors and obstacles to avoid, for example, locked gates.

- Depending on the children’s ages, think about how you might help them to prepare for safety in ways that do not frighten them. Talk to a domestic violence support worker if you need ideas or support about talking to your children about this issue.

- Put some money in a safe place for taxi or bus fares for emergency transport to a safe place. Be careful using rideshare apps if your abuser has access to your account as this could show them where you have travelled to.

- Keep extra keys to your home and car in a place you can easily access if you need to leave quickly.

- Pack all the medications you or your children need or keep the prescriptions somewhere easy to access if you need to leave quickly.

- Know where all your important papers (eg passports, birth certificates, bank details, Medicare card, children’s health records, last tax return, last Centrelink summary, car registration and insurance) are in case you need to find them in a hurry.

- Consider keeping some clothes, medications, copies of important papers, keys and some money at a friend’s house or your workplace.

- If possible, practise travelling to the location you have chosen as a safe place.

- Remember phone and digital safety:

- Use ‘private browsing’ or delete your internet browsing history regularly (if it is safe to do so and won’t escalate your abuser).

- Change your passwords and passcodes, but only if safe to do so. If it isn’t safe, consider what information they may have in accessing your device or online accounts.

- Delete or clear all phone call records to support services or support people from your device call history.

- Review the privacy settings on all online accounts and be cautious in using any accounts shared with your abuser.

- If your abuser has access to your bills, find out if your phone bill will show the phone numbers you have called. This varies between different phone providers.

- Remember the redial number on your landline and mobile phone can be pressed to see what your last call was.

- Get legal advice about separation and domestic violence orders (before you separate, if possible).

- Consider talking to police even if you do not want to take out a domestic violence order, so they are aware of your circumstances.

- Get medical attention and support for any injuries, particularly if your abuser has choked or attempted to strangle you.

Know where all your important papers are in case you need to find them in a hurry.

Know where all your important papers are in case you need to find them in a hurry.

What is domestic and family violence?

Domestic violence behaviour includes when another person you are in an intimate personal, family or carer relationship with:

- is physically or sexually abusive to you

- is emotionally or psychologically abusive to you

- is economically abusive to you

- threatens you

- forces you to do things you do not want to do

- in any other way controls or dominates you and causes you to fear for your safety or wellbeing or that of someone else.

Examples of this behaviour include:

- injuring you, punching you, strangling you, grabbing you around the throat, pushing you, slapping you, pulling your hair or twisting your arms or legs, or threatening to injure you, your children, or any person you care about

- repeatedly calling, texting, emailing you, or contacting you or your children through a social networking site without consent

- damaging (or threatening to damage) your property (eg breaking your phone or punching holes in the walls)

- stalking, following you or remaining outside your house or place of work

- following and/or contacting children, colleagues or family members in an attempt to find you

- monitoring you by accessing your text messages, emails, internet browser history or social networking site without permission

- putting you down or making racial taunts

- preventing, or attempting to prevent, you from leaving

- forcing you to engage in sexual activities without your consent

- getting someone else to injure, intimidate, harass or threaten you, or damage your property

- threatening to commit suicide or self-harm to manipulate you

- threatening you or the children with the death or harm of another person or pet

- threatening to withdraw their care of you if you don’t do something

- coercing you to give them your income or preventing you from keeping your job

- forcing you to sign a power of attorney against your will so they manage your finances

- threatening to disclose your gender identity and/or sexual orientation to your family, friends or colleagues without your consent

- preventing you from making or keeping connections with your family, friends or culture, including cultural or spiritual ceremonies or practices.

If another person you are in a relevant relationship with (see Which relationships are protected?) does any of these things, you can apply to a magistrate at a Magistrates Court for a domestic violence order. It is important to remember you do not have to have been physically injured to have experienced domestic violence.

Children are exposed to domestic violence when they see, hear or experience these behaviours directly or indirectly. (See What about children?).

Who does the law protect?

Which relationships are protected?

The Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act 2012 provides protection from violence for people who are, or have been in:

- an intimate personal relationship (married, defacto, registered relationship, engaged, dating)

- a family relationship (a parent, or former parent, of a child, or your relatives)

- an informal care relationship (where one person is dependent on the other person for help with daily living activities like having a shower, getting dressed or cooking).

Can family and friends be protected?

Yes. Your family, friends, a new partner or workmates can be included on a domestic violence order as ‘named persons’ to protect them. When someone is domestically violent to these people it is called ‘associated domestic violence’.

What about children?

Children, or children who usually live with you or spend time with you, can be included on a domestic violence order to protect them. This could include step- children or other children who spend time at your house on weekends or school holidays. If you are pregnant, you can ask for the order to have a condition that takes effect to protect the child once they are born.

A magistrate must consider including children who have been exposed to domestic violence. The law says a child has been exposed to domestic violence if they hear or see or ‘otherwise experience’ domestic violence. This could include:

- being present when domestic or family violence happens

- helping a family member who has been hurt as a result of domestic violence or

- seeing damaged property in the home.

If children are named on a domestic violence order, it does not replace a parenting order or determine when or how children spend time with either parent. If you have concerns about care arrangements for your children, you should get legal advice.

If you are worried about the safety of your children when they are in the care of the respondent, you can contact child safety authorities to discuss your concerns.

Who is not covered by domestic violence laws?

- Neighbours, housemates or friends cannot apply for a domestic violence order against someone they are not in a relationship with, related to or caring for.

- A parent cannot apply for a domestic violence order against their child if the child is under 18.

- Children under 18 cannot apply for an order against their parents or family members.

Does my domestic violence order protect me throughout Australia and New Zealand?

Orders made in Australia or New Zealand on or after 25 November 2017 will be automatically recognised in both countries and all states and territories.

If you are concerned about a domestic violence order that was made before this date being enforced, call Legal Aid Queensland on 1300 65 11 88 for advice.

If you do separate from your partner and they are sponsoring your visa, you should get urgent legal advice.

If you do separate from your partner and they are sponsoring your visa, you should get urgent legal advice.

If I separate, can I be forced to leave Australia?

If you are an Australian permanent resident or an Australian citizen, you cannot be forced to leave Australia if you separate from your partner.

If you are on a temporary visa, a student visa, or you have applied for a permanent visa, or are sponsored by your Australian partner, then your partner may contact the relevant Australian Government department that oversees immigration if you separate. The government will review your situation. Any decisions about your immigration status will be made by the government and not your partner.

A threat by your partner to make you leave Australia if you separate from your partner is domestic violence.

If you are considering leaving your partner, you should get legal advice about

the impact separation will have on your visa. If you do separate from your partner and they are sponsoring your visa, you should get legal advice urgently because it may be important that you let the government know of these changes before your partner does.

You can get legal advice from the Refugee and Immigration Legal Service on (07) 3846 9300.

What is a domestic violence order?

A domestic violence order helps to protect you, your children and other people named on the order from someone who is violent to you. A domestic violence order will include conditions to stop the respondent from behaving in a way that makes you feel unsafe.

-

If the police have made a police protection notice or applied for a domestic violence order (DVO) to protect you, they will complete the forms needed.*

If not, you need to fill out the Application for a Protection Order (Form DV1) and lodge it at your local Magistrates Court.**

- Forward to item 2 for notes.

- Forward to item 3 for next step.

-

*A domestic violence order (DVO) is an official document issued by the court with the aim to prevent threats or acts of violence and behaviour that is controlling or causes fear. The term domestic violence order includes temporary (short-term) protection orders and final (long-term) protection orders.

** I f you think you need an urgent temporary protection order, speak to the court registry staff, a police officer, or call Legal Aid Queensland.

Form DV1s are available online at www.courts.qld.gov.au or your local Magistrates Court.

-

The police will serve (give a copy of the Form DV1 to) the respondent (the person you need protection from), with the date and court address where the application will be heard.

-

Mention

The first court date is called a mention. This is usually anytime between the same day and up to 4 weeks after the Form DV1 is lodged at court. On the first court date the magistrate will want to know if the respondent has been served by the police, if they are present in court and whether they agree or disagree with a domestic violence order being made. There may be one or more mentions.

A temporary protection order can be made at a mention and will last until the next mention date or contested hearing date.

-

Is the respondent at court for mention?

- Forward to item 6 if yes.

- Forward to item 7 if no.

-

Does the respondent agree to a DVO being made?

- Forward to item 8 if yes.

- Forward to item 9 if no.

-

Has the respondent been served with the Form DV1?

- Forward to item 10 if yes.

- Forward to item 11 if no.

-

The magistrate may make a final protection order.

-

The matter may be set down for a contested hearing. The magistrate may make a temporary protection order.

-

The magistrate may make a final protection order or adjourn the matter to give the respondent time to get legal advice. If the matter is adjourned the magistrate may make a temporary protection order.

-

The matter is adjourned for another mention until the respondent is served with the Form DV1. The magistrate may make a temporary protection order.

-

Contested hearing

If your matter is set down for a hearing, get legal advice as soon as possible. A contested hearing can also be called a trial.

At the hearing, the magistrate will hear your evidence about why you need a final protection order, and the respondent’s evidence about why a final protection order should not be made.

The magistrate will then decide whether a final protection order should be made. A final protection order usually lasts for five years.

View larger/print version of the flowchart above(PDF, 59KB)

How do I get a domestic violence order? What happens in court?

The magistrate will make an order if they accept:

- there has been an act of domestic violence and

- you and the respondent are in one of the relationships covered by the law (see Which relationships are protected?) and

- a domestic violence order is necessary or desirable to protect you.

At the hearing, you may be represented by a police prosecutor, Legal Aid Queensland lawyer, private lawyer or yourself.

At the hearing, you may be represented by a police prosecutor, Legal Aid Queensland lawyer, private lawyer or yourself.

How do I apply for a domestic violence order?

You can apply for a domestic violence order yourself or a police officer, lawyer or authorised person (friend, relative, community/welfare worker) may apply for you.

You should get legal advice before applying for a domestic violence order. Legal Aid Queensland gives free legal advice and may be able to help you apply for a domestic violence order.

How can the police help?

If the police suspect domestic violence has been committed, they must investigate your complaint. If they investigate your case and reasonably believe domestic violence has occurred, they can:

1. Charge the respondent with a criminal offence

The police may charge the respondent with a criminal offence (eg strangulation, stalking, assault, grievous bodily harm) if they believe it would be more appropriate to deal with the behaviour through the criminal law system. If they do charge the respondent with a criminal offence, the respondent’s bail conditions may stop the respondent from having contact with you.

2. Issue a police protection notice

This is issued on the spot to protect you immediately from further acts of domestic violence. It has the same effect as a domestic violence order until the matter is heard in court. Before they can issue a police protection notice, the police must reasonably believe:

- domestic violence has occurred

- you haven’t already got a domestic violence order in place and

- an order is necessary or desirable to protect you.

You should talk to police about whether this applies to your situation.

The police protection notice may include conditions that provide effective and immediate protection for you and your children such as to stop the respondent from coming to or staying in your home, trying to approach you or trying to contact you.

The police may need to notify child safety authorities that domestic or family violence has occurred.

3. Apply to a court for a domestic violence order for you

If a police officer applies to the court for a domestic violence order for you, they will complete the application form and will appear for you in court. You may choose to attend court if you want to make sure all the conditions you need to protect you are made, or you may need to attend some court appearances. If you have questions about attending court, you can talk to the police at your local police station or contact Legal Aid Queensland on 1300 65 11 88.

4. Apply to a court to change an existing domestic violence order

This only applies if you already have a domestic violence order in place. The police can apply to the court to vary (change) the conditions in your existing domestic violence order so you have increased protection.

5. Take the respondent into custody

The police can take a respondent into custody if they believe the respondent is likely to injure someone or damage property.

6. Apply directly to a magistrate for an urgent temporary order

If the police believe you and your children are in immediate danger, and the normal application process is too slow to protect you, they can apply for an urgent temporary protection order. This may also happen if the court is in a remote location, the court does not sit regularly, or the respondent cannot be easily located.

How can a lawyer help?

You can ask a lawyer to help you by contacting your local Legal Aid Queensland office, a community legal centre or a private lawyer for legal advice.

Lawyers can help you at different times during the application process. They can:

- give you legal advice about applying for a domestic violence order in your circumstances

- help you complete your application paperwork

- represent you throughout your court proceedings.

If you want a lawyer from Legal Aid Queensland to represent you, you will need to fill out aLegal Aid Queensland application form and show you meet the criteria for legal aid. Some private lawyers can also apply for a grant of legal aid to represent you. These lawyers are called Legal Aid Queensland ‘preferred suppliers’ and you can find a list of them on our website at www.legalaid.qld.gov.au.

There may be a domestic violence duty lawyer at court to help you. You can check with the court registry to find out if a domestic violence duty lawyer will be available on your court date. You can also visit our website and search for “domestic and family violence duty lawyer”.

Applying for a domestic violence order through an authorised person

If you do not want to apply for the domestic violence order yourself, you can get a friend, relative or community/welfare worker to apply for you. You will need to give that person authorisation to apply for an order for you.

Applying through a guardian

A guardian or administrator, who is appointed under the Guardianship and Administration Act 2000, can apply for a domestic violence order for you.

Applying through the Office of the Public Guardian

If you have a guardian through the Office of the Public Guardian then the guardian may be able to apply for a domestic violence order for you.

Applying through an attorney

A person acting under an enduring power of attorney under the Power of Attorney Act 1998 can also apply for a domestic violence order for you.

If you decide to get someone else to apply for you

If you decide to get someone to apply for a domestic violence order for you, you must give them written authority to do so, unless you are unable to (for example, if you have a physical impairment and cannot write your name). You will need to complete anAuthority to Act ( see page 19 for a sample of this document). The person applying for a domestic violence order for you is called ‘the authorised person’. You need to work closely with this person. The authorised person must fill out all the sections on theDV1 Application for a Protection Order form, especially Part 3, and sign the declaration. The authorisation must be filed at court with the domestic violence application.

View the letter as a PDF(PDF, 59KB)

Preparing your own application

Step 1. Get legal advice and other help

You should get legal advice before you start the process to apply for a domestic violence order.

In some places there are programs to help people apply for a domestic violence order—these include domestic violence prevention programs, application assistance programs or domestic violence services. You can ask at the Magistrates Court about these programs before starting your application.

Step 2. Fill out the application form

To apply for a domestic violence order, you must fill out aDV1 Application for a Protection Order form. You can do this:

- online by visiting www.qld.gov.au and searching “prepare your application for a protection order”

- by downloading the form from the Queensland Courts website and filling it out on your computer, smartphone or tablet

- by printing the PDF form from the Queensland Courts website and filling out the paper copy by hand

- by asking for a copy of the form at your local Magistrates Court.

See the sample DV1 Application for a Protection Order form.

Get help from a lawyer, domestic violence prevention worker, refuge worker or someone who works with people affected by domestic violence when you are filling out the application form.

You can get free legal advice from Legal Aid Queensland about what you need to include in the application form.

What information should I include on the form?

You should describe the domestic violence you have experienced recently. It is helpful to the court to include as much detail as you can, which may include:

- the type of violence

- when it happened or how often it happened

- where it happened

- what happened

- how it happened

- who was there

- any injuries you suffered

- how you felt (eg did you feel threatened, fearful or scared?).

You should give specific details where possible. If you can’t recall the specific date of an incident, you may want to include an estimated date, for example: “on or around 3 December 2019” or “when the football grand final was on”.

If you have experienced the same or similar behaviours over a long period, you may want to describe the behaviour then explain how often it happened and include the dates you can remember, for example: “about every pay day, the respondent would become so angry with me they would become physically violent where they would…”.

Can I keep my address details private?

If you do not want the respondent to know your address and contact details, you can leave the contact details blank on the DV1 Application for a Protection Order form and include them on the Domestic Violence Aggrieved Confidential Address form (see a sample of this form).

What can I do if I have concerns about my immediate safety?

If you have concerns about your immediate safety, you should ask the court to consider immediately making an urgent ‘temporary protection order’. If your circumstances are urgent, your application can be quickly listed to go before a magistrate. This can happen even if the application has not yet been served on the respondent and if you can show it is necessary or desirable for you to have immediate protection. Make sure you have ticked the box for a temporary protection order.

Will the respondent see my application?

The respondent will be given a full copy of your application and all attachments.

Step 3. Gather evidence and attach it to the form

You should also start gathering the information (evidence) you will need to support your application. Information that may be helpful includes:

- photos of any injuries taken at the time the domestic violence happened

- photos of any injuries taken later when they are more visible (like bruising that shows up a day or two later)

- statements from people who saw or heard the domestic violence or who you have told about the domestic violence over a period of time

- diary entries you have made about the domestic violence

- doctors’ reports

- other court orders, eg other domestic violence orders or family law orders

- reports from counsellors who you have seen

- phone call logs of calls made to your phone by the respondent

- all text and voicemail messages, emails, letters and social media entries (printed out with dates).

Attach this evidence to your application form.

If possible, try to use photographs that have a date stamp on them—they can help you remember when the incidents happened. You can attach photographs (or colour photocopies of them) to your application form.

Step 4. Attach any court orders

If you have any court orders, like family law orders about your children, Childrens Court orders or any old or current domestic violence orders, you must attach a copy of these orders to your domestic violence order application form.

Step 5. Sign the declaration

You must sign the declaration on the application form in front of a justice of the peace or a lawyer. When you sign the form, you are indicating the details are true and accurate. All Magistrates Courts have a justice of the peace who can witness you signing your application form. You will need to take photo ID with you.

Step 6. File the application

You must file your completed, signed and witnessed DV1 Application for a Protection Order form at a Magistrates Court registry. There is no cost to file your application form, but you will need to show photo ID to the registry. You cannot submit your application online—if you are filling it out electronically, you will need to print it and file it at the court.

Step 7. Let the court know if you need an interpreter

If you do not speak English, or you do not feel confident with legal terms in English, you should ask the court to arrange an interpreter. You should let the court know you will need an interpreter when you are filing your application form or at your first court appearance. The magistrate will decide whether an interpreter will be used.

What happens after my application form has been filed?

After you’ve filed an application you will be given:

- a court date (as soon as possible), depending on the court’s availability, to ask for an urgent temporary protection order or

- a date to appear at court (usually within about four weeks).

If you need immediate protection, you can ask for the magistrate to make an urgent temporary protection order that starts as soon as your application is served on the respondent. If you want an urgent temporary protection order, you need to fill out that section on the application form (see the sample form).

The clerk of the court will arrange for the police to serve (deliver) a copy of your application and any temporary order on the respondent. You can call or go to your nearest police station to ask if the application has been served on the respondent before you go to court. Even if the application has not been served on the respondent, you will still have to go to court.

What happens at the first court appearance?

Your first court appearance is called a ‘mention’. A mention is a short court appearance where the magistrate will check if your application has been served on the respondent and find out if the respondent agrees or disagrees with your application for a domestic violence order. You do not need to bring any witnesses to the first court appearance.

What happens if I do not arrive on time or do not turn up for court?

If you do not arrive at court on time, your application may be dismissed. If this happens and you still want a domestic violence protection order, you will need to file a new application with the court.

Can I take my children to court with me?

There is no one at the court to look after your children. It is not appropriate to bring children into the courtroom with you.

If you have to bring your children to court, you should bring someone with you to look after them. If possible, try to leave your children with a trusted family member, friend or babysitter.

When you go to court

- Arrive at court 15 to 30 minutes early.

- If you don’t have a lawyer, a domestic violence duty lawyer may be available in some courts. They can give you free legal advice about your court appearance. Check with the court registry before your court date to find out if this is an option for you. Sometimes the police prosecutor may be able to help you in court.

- If you’d like extra support, you can talk to a domestic violence prevention worker who may be available at some courts. Check with the court registry before your court date to find out if this support is available.

- You can bring your own support person to court. The magistrate will decide whether your support person can come into the courtroom with you. Your support person cannot speak for you unless they have made the application for you as an authorised person.

Will I have to see the respondent in the waiting room?

If you are worried about seeing the respondent in the waiting room, contact the court registry about your situation before you arrive. Some courts have a safe room where you can wait before and after your court appearance. Some safe rooms have direct access in and out of the court room. At some courts you can enter and exit the building through the safe room.

If you have concerns about your safety while at court, you can let the court staff know by filling in a Domestic and Family Violence Safety form. This form is available from the Queensland Courts website or at the registry when you file your application. Court staff will give a copy of the form to the security officer, domestic violence prevention worker, the court registrar and any other relevant staff to arrange your safety at court.

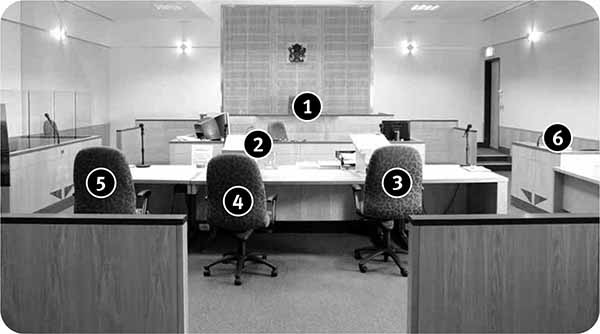

Who’s who in the courtroom?

1. Magistrate — hears the application and decides whether to make the domestic violence order.

2. Depositions clerk — helps the magistrate and records proceedings.

3. Police prosecutor — represents you if it is a police application.

4. Lawyer — represents people in a domestic violence order application in court.

5. Respondent — the person responding to the application for a domestic violence order.

6. Witnesses — people who tell the court about something they heard or saw that is relevant to your application.

What are the respondent’s options?

When the respondent receives their copy of the domestic violence order application they can:

- agree (consent) to a domestic violence order being made; the respondent can only agree to a domestic violence order being made if they are in court when they consent, or through a lawyer or in writing; the respondent can agree to a domestic violence order being made without admitting to the facts—this is called ‘consenting without admission’

- ask for the court proceedings to be adjourned (put off) to another date so they can get legal advice

- oppose the order—if this happens, the court may give you a hearing date

- do nothing (and not attend court).

If the respondent agrees to the orders you want, the magistrate will make the domestic violence order for five years. If there are special circumstances, you can ask the magistrate to make the domestic violence order for more or less time.

If the respondent asks to adjourn your application, you should ask the magistrate to issue a temporary protection order until the next court date.

If the respondent has been served and does not agree with your application for a domestic violence order, the magistrate will give you a date for a contested hearing. This will be a date where you, the respondent and any relevant witnesses may be cross-examined or asked questions about the domestic violence. (See What happens at a contested hearing? for more information about contested hearings.)

If the respondent has not been served with the documents before the first court appearance, the magistrate will adjourn your application to another date, so the respondent can be served with the documents. If you think you will be in danger during that time, you can ask the magistrate to make a temporary protection order for you until the next court date.

What happens if the respondent applies for a domestic violence order against me?

When both parties apply for a domestic violence order against each other, this situation is called a ‘cross application’.

You should get legal advice if there is a cross application.

If the magistrate believes the application is vexatious (being used to cause annoyance), or is without merit, they may dismiss it.

If the respondent opposes your application, there will be a contested hearing at a later date (see What happens at a contested hearing? for more information about contested hearings). The magistrate may transfer the applications so they are heard together on the same date. At the contested hearing the magistrate must consider who is most in need of protection.

If the magistrate gives you a court date for a contested hearing, you should get legal representation from the police prosecutor (if the police are making the application), a private lawyer or a Legal Aid Queensland lawyer. You should organise this as soon as you are given the contested hearing date so there is time to prepare your court material.

What happens if the respondent doesn’t come to court?

If the respondent does not come to court at the required time the magistrate can:

- adjourn the application to another court date

- make a final domestic violence order with the conditions that you asked for in your application (see final orders for more information)

- issue a warrant for the respondent’s arrest.

If the respondent is not at court, and the police can show they have served the respondent, the magistrate can make a final domestic violence order. The magistrate must be satisfied any conditions included in your domestic violence order are supported by enough evidence.

If the respondent is not at court, and the police can show they have served the respondent, the magistrate can make a final domestic violence order.

If the respondent is not at court, and the police can show they have served the respondent, the magistrate can make a final domestic violence order.

What happens at a contested hearing?

If the respondent opposes the domestic violence order, or if you cannot agree about the order’s conditions at the mention, you will be given a new court date for a contested hearing.

If your application is listed for a contested hearing, get legal advice as soon as possible.

A contested hearing allows the magistrate to hear your evidence about why you need a domestic violence order and the respondent’s evidence about why a domestic violence order should not be made.

In most courts, you and the respondent may have to give all your evidence, and the evidence of your witnesses, in affidavits (sworn statements) and exchange these before the contested hearing. This includes supporting evidence like photographs, medical certificates and emails.

It is important you file your affidavits at the court registry and then arrange service of a copy of the affidavits to the respondent by the dates the court has set.

Service is the legal term used to describe giving or delivering court documents to another person in a way that satisfies the court that the person has received them. This is particularly important if the person served does not attend court. If the court is satisfied the person has received the court documents, the case may proceed without that person being present and orders may be made.

Service can be by:

- hand — you may arrange for a process server (for a fee) or any other person over 18 to hand deliver the documents for you; process servers are listed in the Yellow Pages

- registered post — do not do this unless you are confident the other person will sign for the documents

- fax or email — you can do this if the person has given a fax number or email address to the court

- service on a lawyer — a document is taken to be served on a person if they have a lawyer representing them and the lawyer has agreed, in writing, to accept service of the document for that person

- any other way approved by the court.

Courts across Queensland have different practices for service check with the court registry. Get legal advice.

If you do not serve the respondent, your application could be dismissed or you may not be allowed to have the court consider your evidence.

At the hearing, you and any witnesses will have to go to court in person and answer any questions from the magistrate and respondent. If the respondent does not have a lawyer, you can ask the magistrate to not let the respondent cross examine you (ask you questions in court) as it may cause you emotional harm or distress. In these circumstances the magistrate may ask you the respondent’s questions or allow you to be asked questions by video link or from behind a screen.

Who will represent me?

If you cannot afford a private lawyer you should apply for a Legal Aid Queensland lawyer to represent you. If the police are making the application, the police prosecutor will represent you when a contested hearing date is set. You can also represent yourself. For more information about representing yourself at your hearing, see the Representing yourself at your domestic violence application hearing factsheet on the Legal Aid Queensland website.

Will the public be allowed in the courtroom for the hearing?

No. The contested hearing will be held in a closed court, which means the public cannot watch or listen.

Should I bring my witnesses to the hearing?

Yes. You should bring any witnesses who saw or heard incidents of domestic violence to the contested hearing. They will need to answer questions about their evidence in person. Ask your witnesses to write down what they saw or heard as soon as possible after the events and to bring these notes with them to court.

Children cannot give evidence in a domestic violence court unless the magistrate gives them permission to. If you want a child to give evidence before the court, you should get legal advice.

You should also bring any other supporting evidence to the contested hearing. Supporting evidence like photographs of your injuries, medical reports from the doctor who treated you, text messages and phone logs will help the magistrate decide whether to make the domestic violence order.

Will I have to give evidence at the hearing?

Yes. You and your witnesses will give evidence in the court. You will need to tell the magistrate what happened to make you apply for a domestic violence order. Most of the details should have been included in your application and affidavit, so only explain any matters the magistrate asks you about. If you do not have a lawyer, the magistrate will guide you through the evidence process. After you have given evidence, you will be told to call your witnesses into court. Ask them to tell the magistrate what they saw or heard.

When you give evidence, the respondent or their lawyer will ask you questions about your evidence. When the respondent gives evidence, you or your lawyer will be able to do the same. This is called cross-examination. Witnesses will also be cross-examined. The respondent will present their case in the same way.

After listening to the evidence given by you, the respondent and any witnesses, the magistrate will decide whether to give you the domestic violence order you have applied for. The magistrate must be sure:

- you and the respondent were in a relevant relationship

- the respondent did commit an act of domestic violence and

- it is necessary or desirable for you to have a domestic violence order.

Will the respondent get a criminal record if the magistrate makes a domestic violence order?

No. The domestic violence order does not result in a criminal record for the respondent. If the respondent breaches the domestic violence order, they may be charged with a criminal offence.

Are there any costs involved in getting a domestic violence order?

If you have hired a private lawyer, you will usually have to pay for the cost of your own legal representation. There are no costs if a police prosecutor represents you at court. You can apply for a Legal Aid Queensland lawyer if the police prosecutor cannot represent you—depending on your financial circumstances, you may have to make a contribution towards your legal aid costs.

The magistrate may make you pay the respondent’s court costs if they decide to dismiss your application because they believe it is deliberately false, frivolous, vexatious or malicious.

What if I disagree with the magistrate’s decision?

If you disagree with the magistrate’s decision, you can appeal it. You need to file the appeal in the District Court within 28 days from the date the magistrate made the decision about the domestic violence order.

You should get legal advice if you want to file an appeal.

You should get legal advice if you want to file an appeal.

Will the court proceedings be made public?

No. A person is not allowed to publish any information said in a domestic violence court or any information that identifies the applicant, respondent, children or witnesses involved in a domestic violence court proceeding. If they do this, the magistrate can issue a fine.

Information can only be published if the magistrate allows it, or the applicant and respondent agree to it being published, or the publication is for law reporting or research purposes.

What orders can be made by the magistrate?

Temporary protection orders

A temporary protection order aims to give you protection from domestic violence until your application is decided by the magistrate. Temporary protection orders are given if you are in a relationship covered by the law (see Which relationships are protected?) and domestic violence has been committed.

Even if the respondent doesn’t know you are applying for a domestic violence order, the magistrate can still make a temporary protection order. To make a temporary protection order, the magistrate must be satisfied there has been an act of domestic violence and there is a relevant relationship between you and the respondent.

Final protection orders

A final protection order usually lasts for five years. It can be made:

- if the respondent agrees to the order being made or

- if the respondent doesn’t turn up or participate in the court process after being served or

- after a contested hearing in a court.

Domestic violence order conditions

Domestic violence orders automatically include a condition that the respondent must be of good behaviour and not commit domestic violence against you, your children and any other people named on your order.

You can also ask for other conditions on the domestic violence order. The magistrate must consider your safety and your children’s safety when deciding whether to add other conditions to the order.

Other conditions that may be included in a domestic violence order are:

- stopping the respondent from going to where you live or work, or within a certain distance of where you live or work

- stopping the respondent from living with you—get legal advice before asking for this type of order

- stopping the respondent from trying to locate you, for example, stopping them from contacting your family, friends or a place where you are staying (like a refuge or shelter)

- making the respondent give you access to the house you used to live in so you can get your belongings

- stopping the respondent from behaving in a particular way towards your children (or children who usually live with you)—if you are pregnant, this includes your child once they are born

- stopping the respondent from going to places where your children frequently visit, like their school or kindy

- stopping the respondent from having contact with you or other people named on the order—this means the respondent cannot call you, write to you, send you text messages or visit you.

You can ask the magistrate to make an exception to the extra conditions if you want to attend mediation with the respondent, or allow your children to spend time with the respondent.

In some circumstances it is possible for the court to stop the respondent coming back to where you live, or to remove them from where you live, even if you have lived there together. This is known as an ‘ouster’ condition. If the magistrate makes an ouster condition, they must also consider allowing the respondent to return to the residence to get their belongings. The police can supervise the respondent collecting their belongings.

Intervention orders

If a magistrate makes or changes a domestic violence order, they can also make an intervention order requiring the respondent to attend a behaviour change program. A behaviour change program is usually an 8 to 12-week program with counselling that tries to change the respondent’s behaviour. This order can only be made if the respondent is in the court, agrees to the intervention order being made or changed, and agrees to follow the intervention order.

Consent orders

Consent orders can be made if the respondent agrees to your application for a domestic violence order (or agrees to change an existing domestic violence order). The respondent does not have to admit to the facts you have included in the application, or agree with your side of the story, for the court to make consent orders. This is known as ‘consent without admission’. The magistrate will consider your safety, your children’s safety and the safety of anyone else named in your application when deciding whether to make consent orders.

If the respondent is under 18, they may not be able to agree to a domestic violence order. You should get legal advice if this applies to your situation.

If a police officer is acting for you, the magistrate can only make a consent order if they are sure you also consent to the order being made.

Will my domestic violence order affect my existing family law orders?

The magistrate must consider any family law or child protection orders you have before deciding to make or change a domestic violence order. If you have a family law order or child protection order about your children, or if you have proceedings in the family law courts or Childrens Court about your children, you must tell the magistrate, attach a copy of the orders to your domestic violence order application or give a copy to the magistrate.

A magistrate must consider changing your family law order if the conditions in the order:

- conflict with conditions in your domestic violence order and

- could make you, your children or anyone else named in your domestic violence application unsafe.

For example, if your family law order allows the respondent to come to your home to collect your children and these visits lead to verbal abuse, threats or any other act of domestic violence, the magistrate can change the family law order to make the collection point away from where you live. The magistrate can also cancel or suspend your existing parenting order if they are satisfied it would be unsafe for you or the children to continue spending time with the respondent.

If you have a domestic violence order and you have family law court proceedings or Childrens Court proceedings, you must tell these courts about your domestic violence order.

Can a magistrate make a domestic violence order even if they have not received an application for one?

Yes. Sometimes a magistrate can make a domestic violence order against someone even though the aggrieved has not applied for one. This can happen if a magistrate convicts a person of an offence involving an act of domestic violence. To make an order, the magistrate would have to be satisfied the people involved were in a relationship covered by the law (see Which relationships are protected?), an act of domestic violence has occurred, and a domestic violence order is necessary or desirable to protect the aggrieved. If there was already a domestic violence order in place when the offence was committed, the magistrate could change the order by including extra conditions or by changing the domestic violence order length to protect the aggrieved. In both situations, the magistrate still has to allow the people involved to say what they think about the order being made.

The Childrens Court

The Childrens Court magistrate can make or change a domestic violence order to protect a parent when a child protection order application has been made.

The magistrate can make a domestic violence order on their own initiative based on the information before the court, or because one of the parties has made a domestic violence order application. The magistrate has to allow the people involved to say what they think about the domestic violence order being made.

If you have a family law order or child protection order about your children, or if you have proceedings in the family law courts or Childrens Court about your children, you must tell the magistrate, attach a copy of the orders to your domestic violence order application or give a copy to the magistrate.

If you have a family law order or child protection order about your children, or if you have proceedings in the family law courts or Childrens Court about your children, you must tell the magistrate, attach a copy of the orders to your domestic violence order application or give a copy to the magistrate.

Making the order work

After a domestic violence order has been made, the magistrate will explain what the order means to the respondent and what will happen if the respondent breaches (doesn’t follow) the order.

If the respondent knows the order is in place (for example, they were in court when it was made, told about it by a police officer or served with a copy of the order) and they don’t follow the conditions in it, they can be charged by the police.

What happens if the respondent breaches the order?

Only the police can charge the respondent with breaching the domestic violence order. If you think the domestic violence order has been breached, you should write down the details immediately as this may help the police. It will also help the police if you have proof of the breach like:

- text messages

- posts on social media sites

- letters

- photographs

- phone messages

- any diary entries you make.

If you tell the police the respondent has breached the domestic violence order, they must investigate and may charge the respondent with breaching the order.

If the respondent is found guilty of breaching the order, the magistrate can order them to:

- do community service

- be put on a good behaviour bond

- be fined or

- be sent to prison.

If the respondent has been convicted of several breaches, has breached the order more than once, or had any other conviction within five years of the current convicted breach, the magistrate can fine them or sentence them to prison. If you have questions about breaches to your order, contact Legal Aid Queensland for legal advice.

If you think the police have not taken your report about the respondent breaching the domestic violence order seriously or have not acted on your complaints, then you should speak to the officer-in-charge or a police domestic violence liaison officer for that police station or region.

Do I have to follow the conditions in the domestic violence order?

Yes. You should try to follow the conditions set out in the domestic violence order or it may be difficult for the police to prove the respondent has breached the order. For example, if the order says the respondent cannot phone you, you should try not to phone them either. If the order stops the respondent from coming within 50 metres of you, you should not come within 50 metres of them.

How long will the order last?

When a magistrate makes a final domestic violence order, they decide how long it will last. The usual length of a final domestic violence order is five years. A magistrate may make a final order shorter or longer than five years if there are special reasons to do so. Before a domestic violence order ends, you can apply to change the order so it ends sooner or is made for a longer time. You should get legal advice if you decide to apply to change the order.

How long does a police protection notice last?

A police protection notice will last until a court makes a domestic violence order, or adjourns the proceedings without making a domestic violence order, or until the application is dismissed by a magistrate.

Can I change the order?

If you want to change the order’s terms or conditions, you must fill out aDV 4 Application to vary a domestic violence order form (see sample forms). If it is the first court date and a temporary protection order has not been made, you may be able to ask the magistrate to include extra conditions in the temporary protection order. You will need to have enough evidence to support your application to change the conditions.

Remember: If you and the respondent decide to live together again, you should get legal advice about having the domestic violence order changed. The respondent may be breaching the order just by being near you.

After you leave the relationship

You should continue to make your personal safety the highest priority after you have left the relationship and the environment in which you were experiencing violence. Make sure you have the support of family, friends, colleagues or a domestic violence worker during this difficult time.

Sample documents and forms

Sample 1 — Form DV1 Application for a Protection Order(PDF, 670KB)

Sample 2 — Domestic violence aggrieved confidential address form(PDF, 119KB)

Sample 3 — Form DV4 Application to vary a domestic violence order(PDF, 367KB)

Sample 4 — Domestic and family violence safety form(PDF, 237KB)

Note:

- These are sample forms to give you an idea of the information you might need to put in. Do not copy the information on the sample forms. Use them as a guide only and put in the information about your situation.

- You will not need to use all these forms. Only use the ones that apply to you.

- Type your answers or write neatly in black or blue pen.

- Make sure the information you use is correct and always double-check the spelling of the names of other people involved.

Legal words and phrases explained

Adjournment – When a magistrate postpones the court matter to a later date.

Affidavit – A signed written statement made by a person to be used in a court. A person who makes an affidavit must swear an oath that the contents of the affidavit are true or make an affirmation that they are true. It is often used in court in place of verbal evidence.

Affirm – Promising what you say is true – usually because your religion does not recognise taking the oath or you do not have a religion.

Aggrieved – The person who needs a domestic violence order.

Authorised person – A person authorised to make an application for a domestic violence order on behalf of an aggrieved.

Breach – When the respondent breaks the conditions on the domestic violence order.

Childrens Court – A court that hears matters dealing with child protection issues and juvenile crime.

Contest – When the respondent opposes or disagrees with your application.

Cross-examination – When someone giving evidence in court is questioned about their evidence.

Consent orders – When the applicant and respondent agree to an order being made without the magistrate having to make any findings about what actually happened.

Couple relationships – When you have been in a relationship characterised by trust, commitment, dependence and intimacy (not just dating).

Domestic violence – Physical, economic, emotional, psychological, sexual abuse, coercion, domination and control inflicted on you by the respondent.

Domestic violence protection order – An order made by the court that puts conditions on a person and is designed to prevent domestic violence, eg that a person not contact their ex-partner. The term domestic violence order includes short term (temporary) protection orders and long term (final) protection orders.

Evidence – The facts relied on in court to prove a case. This could include your oral or written statements, copies of text messages, emails or social media posts or a doctor’s report.

Family – Relatives of the respondent and aggrieved by blood or marriage (including defacto relationships) such as grandparents, aunts, uncles, step-parents, half-brothers, mother-in-law, parents or children (if they are over 18).

Final order – A domestic violence order made by the magistrate that lasts for up to five years, or longer if there are special reasons.

Informal care relationship – This is where one person is dependent on another for help in their daily living activities because of an illness, disability or impairment. This could include dressing, preparing meals or shopping. This help cannot involve paying a fee.

Intervention order – A court order requiring the respondent to attend an intervention program, perpetrators program or behaviour change program to address their behaviour.

Intimate personal relationship – This is where you are or have been engaged, betrothed, married, in a defacto or registered relationship (a spousal relationship), in a couple relationship or have a child with the respondent.

Magistrates Court – The main court dealing with domestic and family violence matters.

Mention – This is a short court appearance. The magistrate will want to know if your application has been served on the respondent and, if the respondent is present in the court, whether they agree or disagree with a domestic violence order being made. There may be one or more mentions. It is not a hearing.

Named person – A person who is a relative or associate (friend, workmate, refuge worker) of the aggrieved who needs to be covered by the domestic violence order.

Oath – A promise that statements made by a person are true or that the contents of an affidavit are correct made by swearing on a religious book. A person who has no religious beliefs or who objects to making an oath can make an affirmation.

Ouster order – A special condition made in a domestic violence order that means the respondent must move out of your home.

Police protection notice – A notice issued by police to give you immediate temporary protection from domestic violence. The police will normally issue a notice if they are called to a domestic violence incident (for example, if they come to your home). It has the same effect as an order and lasts until the police go to court for you.

Protection order (also see domestic violence order) – A long term court order to stop domestic and family violence.

Protected witnesses – An aggrieved or named child who can ask the court for special arrangements to give evidence such as by video or behind a screen.

Respondent – A person against whom an application for a domestic violence order is made. They are the person who is accused of committing acts of domestic violence.

Service – When an application or order is personally delivered to the respondent by the police.

Spousal relationship – Your spouse is:

- someone you are or were married to

- someone you are or were in a defacto relationship with

- someone you are or were in a registered relationship with

- a parent or former parent of your child.

Temporary protection order (also see domestic violence order) – A short term order that lasts until a final decision is made by the magistrate.

Where to go for help

Legal services

|

Legal Aid Queensland

|

1300 65 11 88

|

|

Community Legal Centres Queensland

|

(07) 3392 0092

|

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Information Line (Legal Aid Queensland)

|

1300 65 01 43

|

|

Violence Prevention and Women’s Advocacy (Legal Aid Queensland)

|

(07) 3917 0597

|

|

Queensland Indigenous Family Violence Legal Service

|

1800 887 700

|

|

Women’s Legal Service

|

1800 957 957

|

|

Women’s Legal Service — Rural, Regional and Remote Line

|

1800 457 117

|

|

Refugee and Immigration Legal Service

|

(07) 3846 9333

|

|

LGBTI Legal Service

|

(07) 3124 7160

|

|

Queensland Law Society

|

1300 367 757

|

|

Aged and Disability Advocacy Australia

|

1800 818 338

|

Government agencies

|

Women’s Infolink

|

1800 177 577

|

|

Centrelink

|

13 28 50

|

|

Child Safety Enquiries and Notification Unit

|

1800 811 810

|

Domestic violence services

|

1800 RESPECT telephone counselling

|

1800 737 732

|

|

DV Connect

|

1800 811 811

|

|

DV Connect — Mensline

|

1800 600 636

|

|

Mensline Australia

|

1300 789 978

|

|

Immigrant Women’s Support Service

|

(07) 3846 3490

|

Contacts for counselling and support services:

|

Lifeline

|

13 11 14

|

|

Suicide Call Back Service

|

1300 659 467

|

|

Ozcare

|

1800 692 273

|

|

Relationships Australia and Rainbow Counselling

|

1300 364 277

|

|

Diverse Voices (LGBTI peer support)

|

1800 184 527

|

Interpreting services

|

Deaf Services Queensland

|

(07) 3892 8500

|

|

National Relay Service

|

1300 65 11 88

|

|

Translating and Interpreting Service

|

13 14 50

|

Last updated 2 January 2024